Chaos Breaks Out in Bengal Madrassa Poll Process

Share

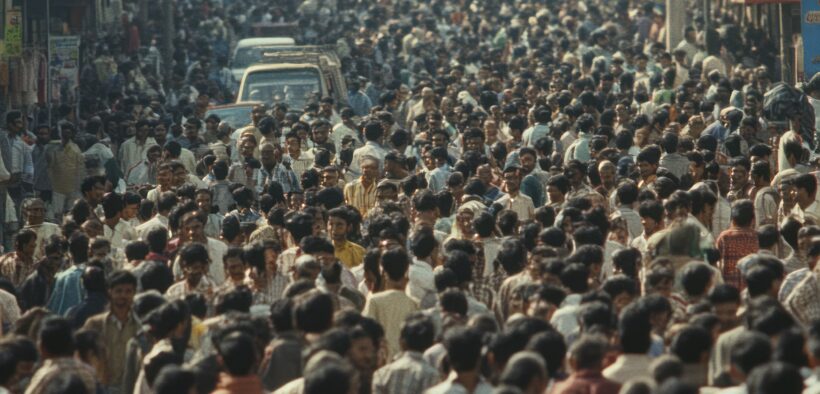

The nomination of candidates for madrassa school committees caused conflicts in various areas of West Bengal, hence exposing the great political divisions that have long hampered the election process in the state. Starting in many places, the violence included injuries, chaos, and accusations of harassment caused by supporters of competing political parties. Since parties regard the madrassa committee elections as a means to measure their strength before more significant political fights, what is generally considered a local custom in educational administration has taken on a very political tone this year.

The filing of nomination papers allegedly turned violent very soon in Murshidabad, Malda, and North 24 Parganas. Reports say supporters of opposing parties started the battle by participating in heated arguments, physical conflicts, and stone throwing outside of particular buildings. Police officers were expected to step in at the sites and, in certain cases, use force to split up crowds and restore control. Many candidates and their supporters said they were refused access to the nomination centers and that their rivals had planned an intimidation plan to stop them from joining.

Strong words have been being used by the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the Left Front, amongst other opposition organizations, following the incidents including the dominant Trinamool Congress (TMC). According TMC leaders, opposition parties seeking to sabotage democracy were unreasonably fixated on TMC candidates. On the other hand, the CPI and its backers contended that the ruling party used force to prevent valid candidates from submitting papers, thereby giving several madrassa committees unopposed victories.

Reports said violence in Murshidabad—a major center for minority education in the state—increased when competing candidates turned in their papers to the same office at the same time. Witnesses said that the atmosphere grew tense as people came together, chanted slogans, and leveled charges. Damage was said to have been done to several of the cars parked close to the store when stones were thrown at them. More security precautions were made known for the following nomination season, and more people needed to travel to the site right away.

Malda remained erratic. Once more, opposition leaders accused organizations linked with the ruling party of employing force and pressure to expel their supporters. Though none of them were, officials believe that at least some of the injuries were shown as life-threatening throughout the battle. Although the administration admitted that sporadic acts of violence had hindered the nominating process, it insisted that continuous observation remained underway.

West Bengal’s madrassa school committees are really crucial as they supervise the running of these institutions, mostly used by the minority population. Because education is such a contentious and politically charged topic, voting for these organizations has grown to be battlegrounds. Political parties view madrasah committee leadership as a means to affect local education policies and get the support of minority communities.

According to observers, the aggressiveness of the confrontations shows how little politics influences local elections in West Bengal. The history of neighborhood activism and competition the state has is reflected in earlier votes for the panchayat, school board, and cooperatives organizations. Parties see this year’s madrassa committee elections as a sign of changing affiliations in places where minority votes have a considerable impact on the outcome of next elections.

Security around important locations under the direction of top police officials was intensified as nominations were received. The government vowed to ensure free and honest elections and declared that any violence would be seriously penalized. Opposition leaders who doubted the government’s equity claimed political pressure had usurped control of it.

Every election-related event, no matter how insignificant, becomes a symbol of larger concerns, therefore exacerbating the already tense political situation in West Bengal. Local village conflicts overshadowed the conventional way of picking representatives to watch madrassa activities. Young people, teachers, and parents, on the other hand, appeared to have opposing views about achieving political influence than about running institutions.

In the days leading up to the elections for these committees, everyone will be watching to see if authorities can guarantee a fair and peaceful process. The events remind one of how closely related politics and education have grown in West Bengal; madrassa committee elections have become yet another flashpoint in the state’s long history of divisive elections.